The diamond revival of the 1930s

Today, three-quarters of brides in America – the world’s biggest diamond market – wear diamond engagement rings, according to Kenneth Gassman, president of the Jewelry Industry Research Institute. It’s hard to imagine proposals were ever otherwise. The diamond solitaire is an enduring symbol of eternal, unbreakable love.

Yet, before 1930, few people proposed with a diamond ring. The concept of an engagement ring had been around since medieval times, possibly even Roman, but was a patchy custom at best. Before the Second World War, only 10% of the engagement rings that were given contained diamonds. That figure had risen to more than 80% by 1990. And for that, we have De Beers to thank. In the late-19th century, the discovery of huge diamond mines in South Africa threatened to flood the gemstone market, swamping a limited demand and crushing prices.

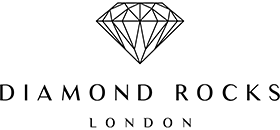

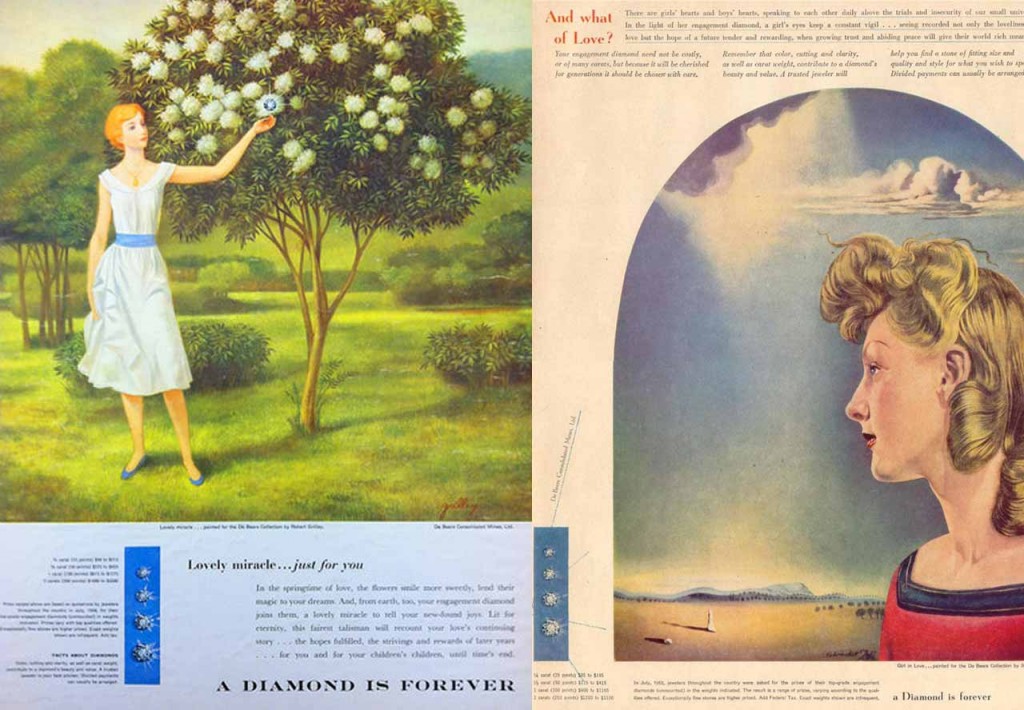

By the end of 1930s, no one in post-Depression America had any cash – certainly not for flippant jewellery – and diamond sales had slumped. So, from 1938, De Beers, then the world’s largest diamond supplier, engaged a prominent, Mad Men-style advertising agency, N. W. Ayer, to cast a spell over the market. They were asked to create a campaign which compelled “every person pledging marriage to acquire a diamond engagement ring.” The agency, with their work cut out, conducted market research and found that most Americans considered diamonds a luxury for the uber-rich. The everyday woman wanted practical gifts – washing machines, cars; diamonds were considered frivolous and wasteful.

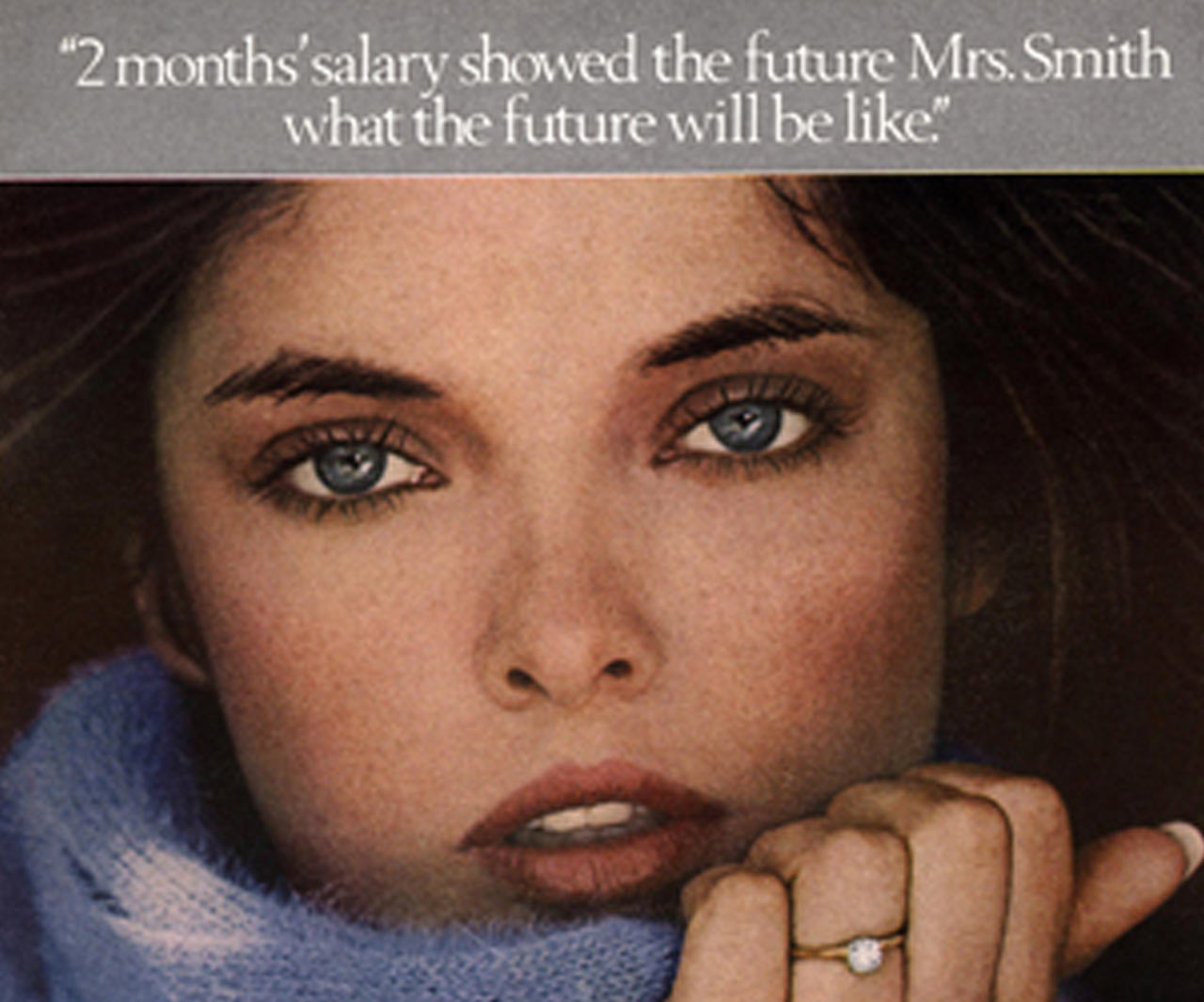

To bend the public to the diamond way of thinking, N. W. Ayer deployed a sustained and multi-pronged marketing campaign to forge an emotional link between diamonds and love. They insisted that a month’s salary was the appropriate sum for a young man to spend on a ring for his beloved. They thrust diamonds under people’s noses, lending glittering jewels to movie stars at the Oscars, and reinforced links between diamonds and romance with celebrity stories in magazines.

They set out to convince lovers that the size of the rock was directly proportional to the ferocity of the affection. They promoted a second diamond (or diamonds) – the eternity ring – to reaffirm passion during marriage. Young copywriter and real-life Peggy Olson, Frances Gerety, came up with the slogan ‘A Diamond Is Forever’, persuading women that the rocks were synonymous with unbreakable romance.

De Beers marketed diamond jewellery with large, global advertising campaigns dictating how many months' salary a man should spend on a ring. It was a master stroke. One that has been slathered over marketing materials ever since. Diamond sales rocketed. Between 1938 and 1941, US diamond sales increased 55%.

When the company eyed international expansion in the 1960s, it merely tweaked the formula. In Japan, where arranged marriages were common and romance less so, diamond rings were marketed as a token of modern Western values, a promise to the bride that her husband would be liberal minded.

When the campaign launched in 1967, fewer than 5% of Japanese women had a diamond engagement ring. By 1981, 60% did, turning the country into the world’s second largest market. Even in the 1990s, people were still falling under the spell. The engagement ring practice barely existed in China in the 1990s; enter De Beers and these days, 31% of Chinese brides wear them.

We still cling to those maxims (or slogans, more accurately), albeit unwittingly, but not just because De Beers told us to. There is a timeless elegance in diamond rings and a huge variety to choose from, both in style and price point. Have a look at our diverse range of engagement rings, from emerald cut to cluster rings and princess and baguette diamond designs, or create a personal one using our bespoke service.